Introduction

You may find it strange to read about PLONK if you haven't read anything about ZKP, and it is, so if you haven't I recommend this other great blog post [1] as an introduction to the topic, or else it's gonna be hard to understand the purpose of this post. I will now assume you have read it, so let's get started.

Now that we all know what ZKP is, the blog post only showed specific protocols that enable us to prove with zero knowledge of particular problems. Nonetheless, it would be interesting to have a general protocol that enabled us to prove any problem, and that's what PLONK is about. We will first think of a way to write the problems more mathematically, and by that I mean instead of having "I know a solution to this sudoku" we will have "I know an input to this function which checks the sudoku validity that returns true". This way we can generalize the problem to any function, and once we have the function we can use the protocol to prove that we know an input that makes the function return true.

Even though the explanation of this topic is usually faced by presenting several mathematical claims and proofs and later using them to build the protocol, I wanted to try a different approach. I will go on and start explaining the protocol and will present all the mathematical claims needed once they are needed. It's true that maybe this way is not the best one to understand the protocol fast, but it is the best one to understand the intuition behind it, and that's what I want to achieve with this post.

From a problem to a circuit

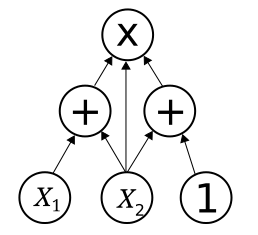

The first thing we will need is to think of a way to work with the problems, and that will be by having them as circuits. Even though there are many circuits and many gates we could build this protocol on, and we will talk about it at the end of the post, the easiest and the one the PLONK paper proposes is the arithmetic circuits. Those are circuits that only have addition and multiplication gates (similar to the ones you may be familiar with, the logic circuits but instead of AND, OR... We have + and *). We can see an example of an arithmetic circuit for the function right here:

How can we convert a problem to a circuit? Let's see an example.

Let's say I want to prove in zero-knowledge that I know the preimage to this value 0x1a2b3c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a4b5c6d in SHA-256. Then we could reformulate this statement by saying I know an input to the circuit such that its output is 0x1a2b3c4d5e6f7a8b9c0d1e2f3a4b5c6d. The circuit we would build here would be the one replicating the SHA-256 function.

Most of the problems we could think of could be reformulated as knowing the input of an arithmetic circuit such that the output is a certain value. Now that we have the problem as a circuit, we can start thinking about how to prove that we know an input to the circuit that makes it return the expected value, all in zero knowledge.

What is needed to prove the statement?

To prove knowledge of the input to the circuit such that the output value is the expected one we will prove the following:

- All the gates in the circuit are computed correctly

- The output of the circuit is the one given to the verifier

- The public input is correctly included in the circuit

- All the connections between the gates are satisfied

If we can prove this without giving any information about the input or the values in each gate, then we will have a zero-knowledge proof of knowledge of the input to the circuit. Our goal in this post will be to build a protocol that solves this, but first, we will have to start from the basics and set some mathematical foundations and notation.

First proof: All the gates in the circuit are computed correctly

To do that, we will have to check if the addition gates output the addition of their respective two input values and the multiplication gates the product of them.

We will be using the same notation the official paper uses, so first of all, let's define a constraint system.

Let's say we have an arithmetic circuit of gates and wires, then a constraint system is defined as follows:

- is the form of where . We can think of as the left, right and output wires of each of the gates.

- where each of the elements in are called the "selector vectors" and they will make sure each of the gates is evaluated correctly.

And we will say that (which will represent the values at each wire) is a valid assignment to if and only if:

This notation and formula out of the blue may seem a bit confusing, but let's see an example to make it clearer and we will see it makes a lot of sense. Let's say we have a circuit with only an addition gate, then we will only have 3 wires, the left, right and output wires. Let's say they have values respectively. Since it's an addition gate we expect them to satisfy . In terms of the previous formula that would mean, we would force the constraints by setting the selector vector for the gate to be . If we now plug in the values of the wires we get:

Which is what we were expecting to have. You may see now how we could force the constraint of a multiplication gate to be fulfilled correctly.

Now we can imagine what these constraint vectors may be like in a larger circuit for addition and multiplication gates. The constrain is the one that will enable us to have the public input in the circuit.

Let's say now we want to prove to our verifier that we got the output of the circuit evaluating all the gates correctly. What we would do is the following:

- We would first get all the values of the wires in the circuit and we would call them .

- Then, consider a multiplicative subgroup of order of , we will call it with generator . We will now generate the following polynomials constructed using interpolation:

- We will also generate the following polynomials constructed using interpolation:

- The verifier will now check if the following equality holds:

If the equality holds, then the verifier will accept the proof. If it doesn't, then the verifier will reject the proof. With this equality, we are checking that the values of the wires satisfy the constraints of the circuit, which is the same as checking if the gates are evaluated correctly.

Now is when we will need to use polynomials commitments to have succinct proof of this equality. In the previous blog post, we saw how the KZG polynomial commitment is built, let's now see what we can prove with it.

ZeroTest on

Let's say we have a polynomial and we want to prove that evaluates to 0 on all the elements of the multiplicative subgroup , which is the problem we are trying to solve. We will call this problem ZeroTest on .

This challenge is solved using a similar idea as the polynomial commitment construction, and we use the lema that is zero in if and only if is divisible by where . This is true since if it is zero in then the values in are roots of the polynomial.

The protocol will go as follows:

- The prover will compute and will commit to it using the KZG polynomial commitment scheme and will send the commitment to the verifier along with the commitment to f.

- The verifier will query the prover for a random point and the prover will send and along with both proofs of correct evaluation.

- The verifier will accept if .

This will work WHP as we saw in the previous blog post, since the probability of two different polynomials evaluating the same at a random point is negligible.

Now we can go back to the original problem and we can see that the previous protocol solves the only problem we had. We can now prove in zero knowledge and in a succinct way (only 2 polynomial commitments are needed) that the equality holds:

That ends the first part of the proof. We now can prove in zero-knowledge the correct evaluation of the gates, but what if the output given by the circuit is not the correct one?

Correctness of the output

This proof is the easiest one as we can just provide the proof using the commitment to . The prover will provide proof of the correct evaluation of at , which is the output of the circuit. The verifier will check that the proof is correct and that the output is the one expected.

The public input is the correct one

We haven't talked much about public input, nonetheless, it is an important part of arithmetic circuits. The public input is the input that is known to the verifier and the prover. For example, if we want to prove that we know the solution to sudoku, the public input would be the numbers that are already in the sudoku.

Out of all the gates, there will be some that will have public input as one of the inputs. We will call these gates public input gates. Consider that is the set of all the public input gates. Then we could just prove that , which is the polynomial that has the value of the public input in , and 0 on the other values of , is equal to the "public input polynomial" . Here is the i'th element Lagrange polynomial basis of , that means that and for .

We can check if this equality holds just by using another zero test on . The prover will commit to and the verifier will check that it is zero in .

We could actually batch this proof with the gate correctness one by doing a zero test on the polynomial:

This way we improve the succinctness of our protocol. We have only one thing to prove to the verifier. And this is that all the wires are correctly treated, which means that if gate 's output is the left input of gate , then we need to check if they are the same value. If we didn't check that, we could have a circuit that evaluates the gates correctly, but just because we are not checking the connections a malicious prover could generate an incorrect proof that would pass the verification with a circuit with most of the gates having 0 values and only the last gates having significant values to output the expected value.

All the connections between the gates are correct

This will be done using the hardest protocol so far, which is the prescribed permutation check. But if we first understand why this protocol is useful in this case, it might make it easier for us to later understand how it works.

This will be done with the extended permutation check, nonetheless, we will first have to explain the permutation check to understand how the extended one works. The main idea is that if we have an output wire that should go to several inputs, we just have to check that the polynomial that has all the wire evaluations and the one that has the wire evaluations permuted (for example cycling the ones that should be equal one to the right) are the same.

For example, in the image at the beginning of the blog, we would check if the output of is equal to the inputs of the left and right gates as well as the gate on top. That would be the same as if we considered the permutation of those wires that has a cycle that goes through all 4 of them (and for this example we could have all the other wires be fixed points), and the polynomial that has all the evaluations, then we would check if . If this was true, then we would be sure that these four wires are correctly connected. Let's build it more formally first, and then we will particularize it to our case.

Prescribed permutation check

This protocol will enable us to prove to a verifier that two polynomials are the same but with the inputs permuted. Consider the polynomials and , and we want to prove that where and is a permutation of .

The first idea that comes to mind is to use a Zero test to prove on . The problem is that this polynomial has degree and the prover can't work with such a big polynomial!

The resulting protocol will be the following:

- V chooses random and sends them to P.

- P builds the polynomials such that and for all . Here \sigma is the permutation that does, but in , that means if .

- P will now compute such that and for .

- V will now check using a Zero test the following:

This will just check that is computed correctly and that . That would imply that the values and are the same just permuted. Which would imply that . If this is not clear you can read the extra part of this blog at the end where I explain it in more detail, as I present another prescribed permutation check that uses the same idea.

This will not be enough though, since we are not checking permutations within one polynomial, but three, which are and . We will need the extended permutation check for that.

Extended permutation check

We already went through the hard part of the blog, as this extended version is pretty similar to the previous one. We will work with the case of checking if and are a permutation of and , but not respectively, since they are permutations of all 3 functions together. To do that we will do the following:

- V chooses a random and sends them to P.

- Let and be polynomials such that and for all and . Here again, is the permutation that does, but in , that means if .

- We now define by

- P will now compute such that and for .

- V will finally check the same two equations as in the previous protocol, but with instead of .

This will check that is computed correctly and that . That would imply that the values and are the same just permuted for all together.

Now we can finish the PLONK protocol by using this extended permutation check to check that and are the permutation of itself. Here the permutation is the permutation that has cycles in all the wires that should be equal because they are connected. By proving that the polynomials are permutations of themselves we are proving that the wires are connected correctly, and thus, that the circuit is computed correctly.

This ends this PLONK protocol. It may take some rereading to fully understand why is this protocol correct since it's a hard topic, but I hope this different approach that I took will help you see the protocol differently and understand it better.

Let's see some interesting properties about this protocol and we will later jump to conclusions.

Correctness, zero knowledge property and extensions

All of the zero-knowledge property relies on the hiding property of the polynomial commitment we use. The correctness and soundness come from the construction of the protocol.

We can see that the only thing that forced us to have addition and multiplication gates is the polynomial equality check that ensures the correct evaluation of the gates, nonetheless, we could have different kinds of gates, even with more than 2 inputs, as long as we check the correct evaluation of the gates.

For example, if we had a gate that given outputs , which we will name new gate, we could just check that:

This could even be extended to having whole hash functions as gates! This makes helps in making the circuit more efficient since we are using the "repetition" property of having personalized gates.

Extra: Another prescribed permutation check

As an extra, I will include another prescribed permutation check, and leave it as an exercise to the reader to find a way to use it to substitute the one we used in the protocol. This one is the one used by Dan Boneh in the ZKP MOOC lecture, and even though it is easier to understand than the one used, I prefer to use the one used in the original paper.

Let's see how to prove that

We make the following claim then, if is a permutation of , then for all . This is because if we have and for a specific and such that they , then that would mean that . If this happens for all values then that means that .

The prover will now build two 2-variate polynomials the following way:

Then as a corollary to the previous claim, we have that is a perm. of .

Now we will just use a Zero test on on and we would be finished!

Conclusion

This is an advanced topic in the cryptography field, and trying to explain it simply is hard. I hope that this article helped you understand the protocol better and that you can now see why each step is needed and why did they find each part. This is nonetheless one of the many SNARKs that exist, based mainly on the KZG polynomial commitment scheme, and therefore bilinear pairings. There are many others based on different assumptions, and if you liked this one, I encourage you to read about others.

Thanks again for reading this article, and I hope you enjoyed it!