A brief introduction to Bilinear Pairings

Bilinear pairings are a very important concept in cryptography, and they are used in many protocols, such as Zero-Knowledge Proofs and Digital Signatures, among others. In this blog post, we will try to understand what bilinear pairings are, and how they are used in cryptography.

A bilinear pairing can be formally defined as a function where and are two additive cyclic groups of prime order q and is another cyclic group of order q written multiplicatively. We also require to satisfy the following properties:

- Bilinearity: and

- Non-degeneracy:

- Computability: There exists an efficient algorithm to compute e.

We won't care much for the computability property, but the pairing we will be building has several know algorithms that enable its fast computation.

We could also have it be a symmetrical bilinear pairing if we require . Today, we will construct a non-symmetrical bilinear pairing known as the Weil pairing.

But why are pairings useful? Our main goal when constructing a bilinear pairing is to have a group with the discrete logarithm assumption (we assume that given , then it is hard to find ) but where the decision Diffie Hellman problem is not hard. This problem can be defined as follows:

- Decision Diffie Hellman: Given and in , determine whether is equal to or not. We say that the problem is hard if it is hard if for any poly-time adversary , we have where , which is the same as saying that the adversary can't distinguish between the real and the random case in polynomial time.

We can easily see that if we can build , then we could solve this problem by checking if and since we require for it to be computable efficiently, the problem wouldn't be hard.

Simple use cases of bilinear pairings

Let's see some use cases of bilinear pairings to fully understand their importance in cryptography.

Digital Signatures

Let's suppose we have a bilinear pairing and a hash function . Consider to be a generator of the group . We can use this to construct a digital signature scheme as follows:

- Key generation: We will generate the secret key and the public key .

- Signature: The signature will be .

- Verification: We will verify the signature by checking . If this is true, then we accept the signature.

We can prove the completeness of this scheme as follows:

We can also prove the soundness of this scheme as long as the discrete logarithm problem is hard in the group and . Since we make the discrete log assumption we can ensure that can't be recovered anywhere from , or .

Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Bilinear pairings in ZKP are an important building block as they allow the construction of efficient polynomial commitment schemes such as KZG, or fast SNARKs such as Groth16.

We will not go into detail on how they are used in these protocols, but I might cover that in another blog post someday. For now, if interested in learning more about this, I recommend the lectures in the ZKP MOOC organized by Berkeley.

Weil Pairing

Now that we have some basic understanding of how bilinear pairings work and why they are important, we will show a step-by-step construction of a specific bilinear pairing known as the Weil pairing. Before we strictly define it, we will have to cover some basic math concepts.

Our first goal will be to have a map where we have linearity on the first component, and just by doing so, we will learn a lot of interesting tools that will be useful once we try to build the full bilinear pairing.

Elliptic Curves

Elliptic curves are a large topic both in mathematics and cryptography, even though it's impossible to cover it all in a blog post, we will try to give a basic introduction to them.

An elliptic curve is a plane curve over the projective field defined by the equation , where is a cubic polynomial with no repeated roots. This definition may sound weird; first of all, what is a projective curve? Let's give a concrete example and define what the homogeneous equation is, and this will help us understand the projective space.

Consider the elliptic curve given by the equation . Let and , then the equation becomes which can be rewritten as . This is the homogeneous (all monomials have the same degree) equation of the curve. Since it is homogeneous we can point out that if is a solution to the equation, then so is ! We could therefore collapse all solutions to a point and consider this to be the representative of all the points in his line. As a convention, we will always consider the representative to be the one where , and if , then we will say that the point is at infinity.

This is called the projective representation of the curve and we can see that there is always a point at infinity, which is always the point that we will refer from now on as .

We have now defined what an elliptic curve is, but why is it useful? It turns out that we can define a group operation on top of it. We define it as follows:

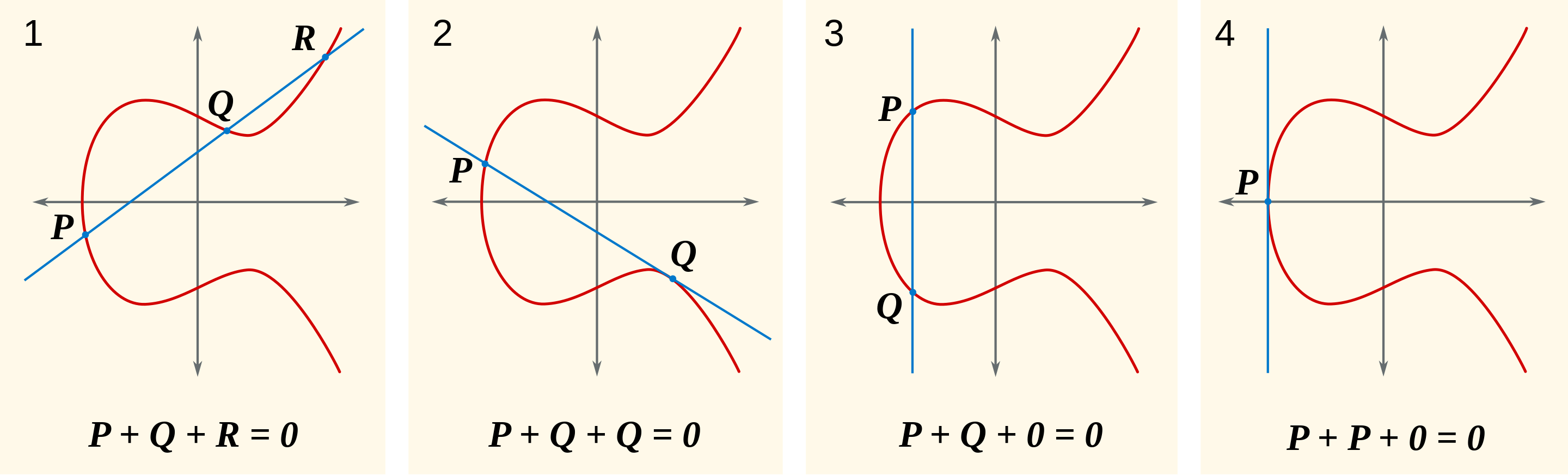

- Group operation: Given three points in the same line , and we say that holds, therefore we have the group operation . It's important to point out that and can be the same point as long as the line is tangent to the curve on , we call that a point of multiplicity 2.

It can be proven that it is well defined (any line through any two points (or one point with multiplicity 2) in the curve will intersect the curve at a third point) and transitive and therefore the group operation is valid but it's a complex result and will not be covered in this post.

Here we have an image to get an intuitive grasp of addition on an elliptic curve over the real numbers:

The image shows how addition behaves over the real numbers, nonetheless, curves can be defined over more abstract fields. We will work from now on with elliptic curves defined over finite fields.

Back to Weil pairing

After this brief elliptic curve introduction we can specify what will groups , and be in the case of our first approach where we will have linearity on the first component. Consider to be a prime number, then we have:

- and are both elliptic curves where the points satisfy the equation over the field .

- is the multiplicative group in .

We can now see why we specified and as additive groups since the operation in elliptic curves by convention is written as an addition, whereas for the multiplicative group in we will use the multiplicative notation.

Even though we have already found where are we going to be working, we still need some more math tools to be able to construct the Weil pairing.

Some more math concepts: Divisors

A divisor is an alternative way to construct a function by specifying its poles and zeros. Poles are points where the function lies at infinity and zeros are points where the function evaluates to zero. Let's see an example for a better understanding.

Consider , which has two zeros: and . If we were given only the zeros, we would be able to reconstruct the function by just having . The same can be said for rational functions, for example, has the same zeros and a pole at . We could now find by multiplying the zeros and dividing by the poles: .

The notation used for divisors is where are the poles and zeros and their multiplicity (negative if it is a pole and positive if its a zero). In the previous rational function example we would have .

The key part of this is that we can also construct functions on the projective plane by defining curves with a similar idea!

Let's say we have the curve whos homogenized version is . We can now find the zeros and poles (in the projective curve, poles are points at infinity, which are points with ). The zeros are and . The poles are and . We can now construct the divisor .

To simplify the notation we will consider all infinities to be equal (even though they are not) and we will write . And even though this doesn't define a curve, any curve that has this amount of points at infinity will serve our purposes.

Observe that if we have a function that has , then has:

Since the multiplicities are added when exponentiating the function.

An interesting fact about divisors is that if they define a curve in a projective plane, then the sum of the multiplicities of the poles and zeros is 0. This is called the degree of the divisor and it's denoted as . It is a consequence of Bezout's theorem.

Another interesting and useful theorem that we will use a lot is the fact that if you "remove" the brackets from the divisors, the points will add to infinity. For example, if we have , then we have (All points at infinity are the same).

The fascinating thing is that if we have a divisor that follows this previous rule, then it is the divisor of a function! This is a consequence of the Riemann-Roch theorem and it's a very important theorem in algebraic geometry. We will use this theorem to make sure that the divisors we use are the divisors of a function we can later reconstruct.

Back to Weil pairing: Bilinearity on the first component

Recall the groups , and from before. Lets say is the order of , then we define the following functions:

Here and are general points in . Thanks to the theorem in the previous section, we know that these are the divisors of some functions since group has characteristic and therefore for any point .

Now lets consider the function which has the following divisor:

Therefore we have a function with which looks a lot like the one with or ! We can now say that and that means the functions are equal despite a constant factor, that we can consider to be if we pick the functions the right way. Therefore we have:

That starts to look a bit linear... but we are not there yet. What we lastly need to get linearity in one coordinate is a procedure named "final exponentiation".

Consider where is the order of the multiplicative group , therefore . We can see here a requirement for which is to have order such that . If we were to raise to z any element that has been previously raised to , we would get 1. Therefore we can consider

Finally we can construct the pairing , then we would have linearity in the first component since

Let's see now how can we fix some things to have bilinearity and be able to claim that we have a bilinear pairing.

Isogenies

We got to the point where math starts getting a bit trickier. Whenever we have defined a concept, for example, vector spaces or topological spaces, then the next item in the list is to talk about maps between those types of spaces. In this case, we will talk about maps between curves which are called isogenies.

The formal definition of isogeny is a morphism of algebraic groups. We will not go into the details of what this means, but we will be using it in the context of elliptic curves. For elliptic curves, isogenies are maps from to , both of them elliptic curves, such that the point at infinity is mapped to the point at infinity.

The only isogeny we will use throughout this article is the following:

As a corol·lary to the Rieman-Roch theorem, we know that a morphism is either constant or surjective. It can be easily proven that this isogeny is not constant and therefore is surjective.

We can also check that and therefore sends the point at infinity to the point at infinity.

This isogeny will enable us to define the m-Torsion subgroup of an elliptic curve for as the points that, multiplied by , give the point at infinity. More formally we have the m-Torsion subgroup of as:

Finally, we will give a definition of the function , which is a particular case of a bigger mathematical concept that will again only need to understand with . If we consider to be the set of divisors from the points of , then this function is defined as follows:

Yeah, this is starting to get messy, but this is not a random definition, we are mapping a divisor of a point to the sum of divisors of the points that map to the original point with . This will help a lot when defining the Weil pairing. Let's see a concrete example to fully understand the last definitions.

Consider , then we know that and therefore is a point of order . Consider the divisor which is a divisor of a function since and a theorem mentioned in a previous section proves the existence of such function.

Consider now such that . We can ensure this exists since we saw before that is surjective. Then we can consider the divisor . Let's study this last equality a bit more thoroughly.

In the first place, we have to see that which is true since . We also know for a fact that if is a coprime to the order of the field the elliptic curve is working on, then the m-torsion subgroup has elements. Therefore we can check that

and we can again ensure that there exists a function such that . This example gave us some intuition on how isogenies and divisors can be used to build functions that fulfill some properties. But the thing is that the example was one of the building blocks of the Weil pairing and will be used next section.

Finally, back to Weil pairing: Bilinearity on the second component

We finally have all tools needed to finish building this pairing. Let's consider these last two functions, where here m is not the order of the group like it was when we got linearity on the first component, but an integer coprime with the order of the field the elliptic curve is defined on:

- such that

- where is a point such that

This looks a lot like the example we saw in the last section! We can see now that

Both functions and have the same divisor and therefore differ by a constant. Let's consider then such that the equality holds and we will have:

Now, for any and , we can see that

And therefore we know that where are the roots of unity of . But

is a morphism (since E is smooth) which is either constant or surjective, but we proved that the images are roots of unity and which implies that this morphism is constant.

Therefore is constant on !

To achieve linearity on the second component we will have to change a bit the group we worked on in the first part of the blog and we will have to start working on the m-Torsion subgroup of , for coprime with the order of the prime of the field the elliptic curve is defined on.

We will finally define the Weil pairing as follows:

Remember that is hidden in the definition of the function and this is one of the reasons why this pairing es expensive to compute!

Lets now prove linearity on the second coordinate:

The last equality uses the fact that is constant on and therefore we can consider in the first fraction.

Now we may think we have finished, but we still have to prove linearity on the first component! We changed too much stuff from the previous approach and we may have lost this property. Let's see that we have not.

It can be proven that the Weil pairing can be written in another way as

From where we can see that and therefore we have linearity on the first component by the fact that we proved linearity on the second component. The proof of the equivalence of both definitions of the Weil pairing is out of the scope of this blog, but it can be found in [5] in theorem 7.

Conclusion

We have made it to the end! If you understood everything, congratulations, it took me days to fully get a basic grasp on it and that is what pushed me to write this blog to make the explanation as simple as possible and have it all gathered in one source.

I tried to give some intuition on why we do each thing and why it works, but I may have failed in some parts. If you have any questions or suggestions, please let me know and thanks for reading!

References

[0] Lectures about arithmetic on Elliptic Curves by Alvaro Lozano-Robledo

[1] Stanford notes on Tate Pairing

[2] Vitalik Buterin's article on Exploring Elliptic Curve Pairings

[3] Stackexchange question about divisors for curves