Ball sorting puzzle game

The ball sorting puzzle is a game that has been played a lot lately on smartphones and may sound familiar. It consists of several tubes with colored balls in them (that we can think of as stacks), and the main goal is to have all the balls of the same color in the same tube. The only allowed operation is to move the top ball from one tube to another.

Even though this version of the puzzle is the standard one, it has not been proven if finding a solution in steps is NP-complete. However, there is a variant of the puzzle that has been proven to be NP-complete, and it is the one we will use in this post. This variant adds a new constraint: the top ball of a tube can only be moved to a tube that is either empty or has a ball of the same color on top.

Having a protocol for the first version would also be useful, nonetheless, it is always more interesting to have protocols for NP statements.

Since the problem is NP-complete, there exists a polynomial time reduction to the 3-coloring problem, which has a simple ZKP protocol[1]. This means that we could build a ZKP proof by solving the reduced 3-coloring problem, nonetheless, this would be a bit boring and the reduction is not always trivial or short. Instead, we will build a ZKP protocol for the ball sorting puzzle directly and by using cards, so it can be executed just with a simple card deck.

Idea of the protocol

It is clear that if we show that we do each step correctly without showing each specific step, and when we finish after steps all colored balls are in the correct tube, then the prover has proven to the verifier that he knows a solution to the puzzle in steps. Here a step is to move a ball from one tube to another, and therefore we have to proof the following:

- The prover is moving a ball from the top of a tube to the top of another tube that is not full.

- The prover is moving a ball to a tube that is either empty or has a ball of the same color on top.

We will design three protocols, one for each proof.

Prelimineries

We will be using playing cards to work on the protocol, so it will be possible to simulate it at home without any computer power.

We will first define as the stack of cards that are:

- if then all cards are 0 but card number on the stack that is 1.

- if then all cards are 0.

- if then all cards are 1.

For example would be the stack of 4 cards that are , would be the stack of 4 cards that are and would be the stack of 4 cards that are .

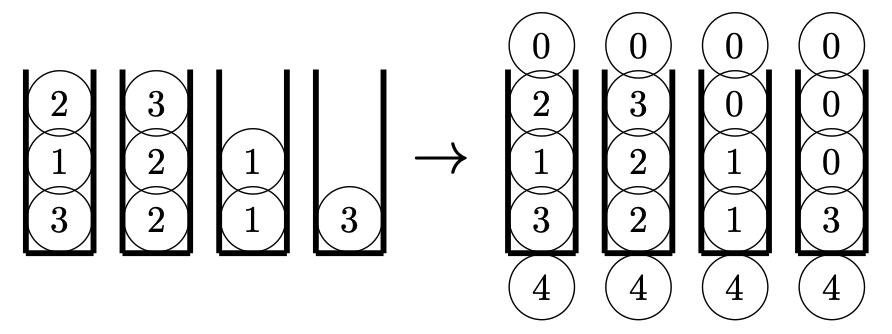

Consider that we have filled tubes (and therefore different colors (we will imagine colors as values from 1 to n)), each tube is of height and we also have empty tubes that we can use to move balls around. Throughout the protocol, we will imagine the empty spaces as balls with a value of 0. We will also add a ball with the value 0 on top of the tube and a ball with the value at the bottom of the tube. This will help simplify the protocol.

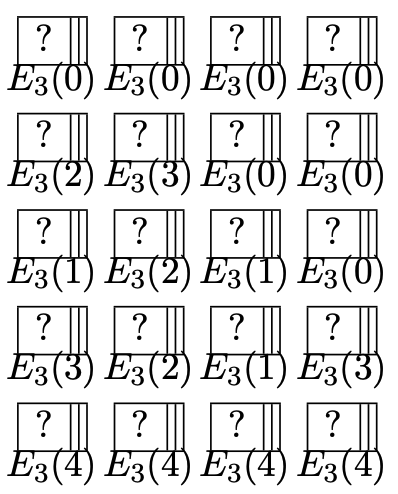

How do we represent this using playing cards? For each ball in this new representation of the problem, we will have the stack , where is the value of the ball. We will therefore have a matrix of stacks of cards of size . They will all be upside down so that the verifier can't see any value of this matrix of stacks. For the previous example we would have the following matrix:

We are all set to start with the first proof.

Protocol 1: Prover is moving a ball from the top of a tube to the top of another tube

This is the same as showing that we are swapping a ball with a value different than 0 or that has a ball with 0 on top of it with a ball with a value 0 that has a ball with a value different than 0 below it.

When thinking with stacks of cards, we will have to prove that we are swapping a stack of cards that is not or , that has a stack of cards on top of it with a stack of cards that has a stack of cards below it. Here we have and values from 1 to .

It would be trivial as a prover to show the verifier the four stacks mentioned above and for the verifier to check if they are valid. Nonetheless, this wouldn't be zero knowledge. This is why we have to think a bit more about how to work the protocol.

The intuition behind the idea is to shuffle the columns of the matrix and then show the verifier the two stacks from the columns we are swapping. This way the verifier can't know which columns the stacks we are swapping belong to. Nonetheless, the verifier will still know the height of the two values we want to show, and therefore if we were to just show the stacks we want to swap, he would still have some information. This is why we now shuffle each of the two stacks we have to show, but this time we maintain the cyclic order, which means we will just shift all the stacks in the column by a random number of positions. This way the verifier will not know the height of the stacks we are showing him.

Now we show the verifier the stacks and , which are the same as and but in the new permutation. The verifier will check if is not or and that is . We will also show that is and is not ( and are modulus ). This way the verifier will know that we are swapping the stacks and .

We have now proven that we are swapping two stacks, one of them with a ball value and one of them with the empty value, the first one having no ball on top and the second one having a ball or a value on the bottom.

To prove that we are not moving a ball to a full stack, we will check if the value on top of the empty value we are swapping is in fact, another empty value. This means we have to check if is . If it is not, that would imply that is , which would mean that the stack is full. This would mean that we are moving a ball to a full stack, which is not allowed.

We can now move on to the second proof.

Protocol 2: Prover is moving a ball to a tube that is either empty or has a ball of the same color on top

This would be the same as showing that the stack right below the value stack we are swapping is either the same stack as the one we swap, or the stack with all 1(the bottom stack). If we consider to be (the stack for a ball of value ), then it would be enough to check that the card in position from both stacks and is a 1. That would imply that either the stack is the same as or that it is the stack with all 1.

This may sound correct but we are leaking information about what color is the ball we swap on the ith step. The solution to that will be to use a protocol called the Color Checking Protocol.

Color Checking Protocol

This protocol enables us to check the following: Given two sequences and ($0 \leq x_1, x_2 \leq q+1) and

- either or

without revealing any other information.

The protocol is as follows:

- Construct the following matrix :

- In Row 1 place the sequence

- In Row 2 place the sequence

- In Row 3 place the sequence

- Shuffle the columns of M such that the cyclic order is maintained.

- Show that in Row 1 there is only one card with value 1 by showing all cards. Suppose the 1 is in position . This proves that .

- Reveal the card in position in Row 2. If it is a 1, then either or .

- Shuffle again the columns of M such that the cyclic order is maintained.

- Finally reveal the third row and use it to revert to its original form.

This may sound complicated but it is clear intuitively that this proves the required claims and maintains zero knowledge. The idea of having a third row to keep track of the shuffling and be able to revert it to the original form is interesting and is used in the different proofs when we have to shuffle the stacks. We won't go into detail with the other shuffling protocols since they are similar to this one, and I thought this one was the most interesting to deeply explain.

Now that we have this Color Checking protocol we can use it to prove that the prover is moving a ball to a tube that has a ball of the same color on top (case ) or is empty (case ).

This ends the protocol as we have now proven that the prover is moving a ball to a tube that is either empty or has a ball of the same color on top.

To show the whole zero-knowledge proof we would have to prove the validity of each step by using the last two protocols, and finally reveal the stacks to show that they are in the correct ending position.

Conclusions

This blog post shows a cool physical zero-knowledge proof presented in [0], but I mainly wrote it since it contains some ideas that can be extrapolated easily to other physical protocols, such as the shuffling techniques used to maintain zero knowledge and how to revert it to the original state.

This is also my first zero-knowledge blog post and I thought that a physical protocol would be a great way to get a grasp on how zero-knowledge is obtained and how can it be used in simple tasks. Nonetheless, the zero-knowledge used in cryptography is built on top of a more complicated structure that enables us to generate proofs for any general circuit. I will write some blog posts later in the future about what circuits are and how can we generate proofs for them, but since there is a lot of information online about it, I will try to find an interesting way to present it.

I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new!